Earlier today, Apple lost a major case when District Judge Denise Cote ruled that the company led a conspiracy to raise e-book prices above those charged by Amazon. Cote's 160-page ruling, released this morning, offered some intricate detail on just how that conspiracy worked.

Cote described how Apple struck agreements with each of the five publisher defendants—who settled the case before trial—in order to push e-book rates higher than Amazon's. The negotiations happened in the seven weeks leading up to the January 27, 2010 announcement of the iPad.

Publishers told Apple they were unhappy with Amazon's standard price of $9.99. Although they received the full wholesale value of each book sold by Amazon, publishers didn't want $9.99 to catch on as the new default price for e-books, especially since this was so much lower than hardcovers. One strategy they used to keep revenues up was to delay the release of e-book versions of new books, but Apple told publishers it opposed this tactic in its then-forthcoming e-books store. HarperCollins wanted to flat-out charge as much as $18 or $20 for e-books, but Apple Senior VP Eddy Cue also made it clear that this was unrealistic. Apple was more amenable, however, when HarperCollins suggested using an "agency model" instead of the wholesale model used by Amazon.

With a wholesale model, Apple would purchase e-books and resell them at a price of its choosing, whereas with an agency model "a publisher sets the retail price and the retailer sells the e-book as its agent." Apple would become the agent selling the books, taking a 30 percent commission on each sale, just as it does with its App Store.

But Apple did not want to open an e-book store at all unless it was profitable, Cote wrote, and in order to make it work, the company had to deal with Amazon. Apple had even considered proposing a partnership with Amazon, "with iTunes acting as 'an e-book reseller exclusive to Amazon and Amazon becom[ing] an audio/video iTunes reseller exclusive to Apple,'" Cote wrote.

"Apple realized, however, that in handing over pricing decisions to the Publishers, it needed to restrain their desire to raise e-book prices sky high," Cote wrote. "It decided to require retail prices to be restrained by pricing tiers with caps. While Apple was willing to raise e-book prices by as much as 50 percent over Amazon’s $9.99, it did not want to be embarrassed by what it considered unrealistically high prices."

Most Favored Nations

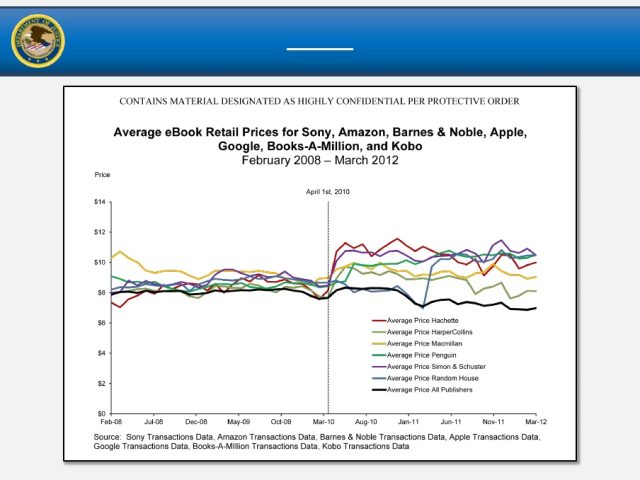

The agency model (along with publisher-set but capped prices of $12.99 to $14.99) made it profitable enough for Apple to open its own e-book store—so long as Amazon's prices went up, too. Apple thus devised a Most Favored Nation (MFN) clause in its contracts with publishers which "guaranteed that the e-books in Apple’s e-bookstore would be sold for the lowest retail price available in the marketplace," Cote wrote. For the publishers to charge up to $14.99 for e-books on Apple's iBooks store, they had to raise prices on Amazon's Kindle store as well by collectively forcing Amazon to accept the agency model.

The MFN approach "eliminated any risk that Apple would ever have to compete on price when selling e-books, while as a practical matter forcing the Publishers to adopt the agency model across the board," the judge wrote.

Amazon, which had nearly 90 percent of the e-book market, resisted the publishers' demands to move to abandon the wholesale model. (Amazon apparently wanted to subsidize content prices, in part, so that it could move e-reader hardware and spur the adoption of e-books by mainstream users.) It retaliated against the demand by removing the "buy" button on Amazon's site for Macmillan books after Macmillan proposed a new agency model deal. Amazon also offered authors a “new 70 percent royalty option” for e-books with a list price “between $2.99 and $9.99," eliminating the middleman and giving authors higher profits.

Amazon could not stand firm for long, however, because the publishers all insisted on new terms more favorable to them. "Attempting to leverage its Apple negotiations to get a better deal with Amazon, HarperCollins included a proposed retail price for the majority of titles at either $12.99 or $14.99, but a commission of just 5 percent for Amazon," the judge's decision states. "HarperCollins then leveled its threat to Amazon. If Amazon declined its offer, HarperCollins would delay for six months the release of any e-book sold on a wholesale basis." Others publishers made similar proposals, but all insisted on agency.

Amazon Kindle Content VP Russell Grandinetti testified at trial that “[i]f it had been only Macmillan demanding agency, we would not have negotiated an agency contract with them. But having heard the same demand for agency terms coming from all the publishers in such close proximity... we really had no choice but to negotiate the best agency contracts we could with these five publishers.”

In Cote's view, this was nothing less than a concerted effort to raise prices—a conspiracy. She summarized Apple's responsibility for the whole situation this way:

A chief stumbling block to raising e-book prices was the Publishers’ fear that Amazon would retaliate against any Publisher who pressured it to raise prices. Each of them could also expect to lose substantial sales if they unilaterally raised the prices of their own e-books and none of their competitors followed suit. This is where Apple’s participation in the conspiracy proved essential. It assured each Publisher Defendant that it would only move forward if a critical mass of the major publishing houses agreed to its agency terms. It promised each Publisher Defendant that it was getting identical terms in its Agreement in every material way. It kept each Publisher Defendant apprised of how many others had agreed to execute Apple’s Agreements. As Cue acknowledged at trial, “I just wanted to assure them that they weren’t going to be alone, so that I would take the fear awa[y] of the Amazon retribution that they were all afraid of.” As a result, the Publisher Defendants understood that each of them shared the same set of risks and rewards.

Why publishers accepted less money from Apple

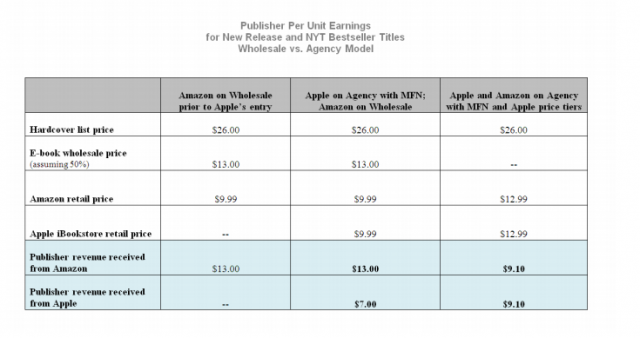

Somewhat counterintuitively, the agency agreements actually lowered the amount of money each publisher received per book. While wholesale agreements gave publishers about 50 percent of the hardcover list price on e-book sales, Apple's agency deals provided 70 percent of the final e-book retail price. This ended up being a significant cut in real dollars.

Cote explains:

[A] Publisher might receive $13 on a wholesale basis for an e-book sold by Amazon for $9.99, but (because of the MFN) only $7 from Apple so long as Amazon was still selling that e-book for $9.99. Even if Apple and Amazon were on the same agency arrangement with a Publisher, and that Publisher were able to move the retail price of the e-book to the top of the Apple price tier and sell it for $12.99, the Publisher would still receive less revenue under the agency model: $9.10 instead of the $13.00 in revenue under the wholesale model.

This chart from Cote's ruling illustrates the pricing and payment breakdowns:

Agreeing to agency models still suited the publishers' long-term interests because they wanted to "shift their industry to higher e-book prices to protect the prices of their physical books and the brick and mortar stores that sold those physical books," Cote wrote, adding that "[t]o change the price of e-books across the industry ... the Publishers would have to raise Amazon’s prices."

Random House, the largest publisher, resisted Apple's call to adopt the agency model in 2010. But the company capitulated a year later in order to get its books on the iPad.

"Apple decided to pressure Random House to join the iBookstore," Cote wrote. "As Cue wrote to Apple CEO Tim Cook, 'When we get Random House, it will be over for everyone.' Apple had its opportunity in the Fall of 2010, when Random House submitted some e-book apps to Apple’s App Store. Cue advised Random House that Apple was only interested in doing 'an overall deal' with Random House. By December, they had begun negotiations, and Random House executed an agency agreement with Apple in mid-January 2011. In an e-mail to [Steve] Jobs, Cue attributed Random House’s capitulation in part to 'the fact that I prevented an app from Random House from going live in the app store this week.'"

The switch to an agency model also impacted Google, which had plans for an Android e-book store of its own.

"Before January 2010, Google understood from its discussions with the Publisher Defendants that the parties would use the wholesale model to sell digital books. But, in January 2010, each of the Publisher Defendants did an about-face and suddenly advised Google that they were switching to an agency model and would no longer be offering books under wholesale terms," Cote wrote. "Google, like Amazon, would have preferred to use the wholesale model and set the retail prices for its e-books, but the Publisher Defendants refused to allow it that option."

Steve Jobs’ role in the conspiracy

When Steve Jobs announced the iPad in January 2010, he demonstrated purchasing a book from the iBookstore. Cote writes:

When asked by a reporter later that day why people would pay $14.99 in the iBookstore to purchase an e-book that was selling at Amazon for $9.99, Jobs told a reporter, “Well, that won’t be the case.” When the reporter sought to clarify, “You mean you won’t be $14.99 or they won’t be $9.99?” Jobs paused, and with a knowing nod responded, “The price will be the same” and explained that “Publishers are actually withholding their books from Amazon because they are not happy.”

With that statement, Jobs acknowledged his understanding that the Publisher Defendants would now wrest control of pricing from Amazon and raise e-book prices, and that Apple would not have to face any competition from Amazon on price.

The import of Jobs’s statement was obvious. On January 29, the General Counsel of S&S [Simon & Schuster] wrote to [Simon & Schuster CEO Carolyn] Reidy that she “cannot believe that Jobs made the statement” and considered it “[i]ncredibly stupid.”

Justice officials prosecuting the e-book case pointed to e-mails from Jobs demonstrating his role in pressuring the publishers. "Compelling evidence of Apple’s participation in the conspiracy came from the words uttered by Steve Jobs, Apple’s founder, CEO, and visionary," Cote wrote, then brought out the puns. "Apple has struggled mightily to reinterpret Jobs’s statements in a way that will eliminate their bite. Its efforts have proven fruitless."

Cote references e-mails Jobs sent to James Murdoch of News Corp., owner of HarperCollins. While Apple's agency model would pay publishers less per book than HarperCollins received from Amazon, Jobs told Murdoch that the anticipated iPad sales would make the model more than worth it. "We will sell more of our new devices than all of the Kindles ever sold during the first few weeks they are on sale," Jobs wrote. "If you stick with just Amazon, B&N, Sony, etc., you will likely be sitting on the sidelines of the mainstream e-book revolution."

Jobs urged Murdoch to "throw in with apple and see if we can all make a go of this to create a real mainstream e-books market at $12.99 and $14.99." The only other alternatives, Jobs wrote, were to "Keep going with Amazon at $9.99" or to "Hold back your books from Amazon," which would lead to piracy.

Links in a chain

In its opening statement, Apple identified five "essential links" the plaintiffs had to establish to prove Apple led the conspiracy. These links, Cote wrote, were that the publishers signed Apple’s agency agreements with an MFN and price caps, that the MFN sharpened the publishers' incentives to demand agency agreements from Amazon, that the agency demands convinced Amazon of the futility of resistance, that Amazon agreed to agency deals in circumstances in which it would not have if not for the Apple MFN, and that publishers raised prices to the price caps as per the agreements with Apple.

"All of the 'links' that Apple identified in its opening statement were established at trial, and Apple did not argue otherwise in its summation," Cote wrote. "Apple similarly abandoned by summation its theory that Apple was unaware that the Publisher Defendants would use their new pricing authority to raise e-book prices; over the course of the trial, Apple’s witnesses admitted that they expected the Publisher Defendants to raise their e-book prices to Apple’s price caps."

DOJ Antitrust Division Chief Bill Baer applauded Cote's decision. “As the department’s litigation team established at trial, Apple executives hoped to ensure that its e-book business would be free from retail price competition, causing consumers throughout the country to pay higher prices for many e-books," Baer wrote. "The evidence showed that the prices of the conspiring publishers’ e-books increased by an average of 18 percent as a result of the collusive effort led by Apple. Companies cannot ignore the antitrust laws when they believe it is in their economic self-interest to do so. This decision by the court is a critical step in undoing the harm caused by Apple’s illegal actions."

As we noted in our earlier story, Apple already said it plans to appeal. "Apple did not conspire to fix e-book pricing," the company said. "When we introduced the iBookstore in 2010, we gave customers more choice, injecting much needed innovation and competition into the market, breaking Amazon's monopolistic grip on the publishing industry. We've done nothing wrong."

reader comments

253