I recently came upon Survivor Library, an archive of scanned books collected by Rocky Rawlins, who describes himself as not a “prepper in the traditional sense,” but has a deep interest in maintaining and distributing volumes that describe practical skills that would still be useful after an EMP hits. Survivor Library doubles as a fascinating archive of practical old nonfiction books, covering topics from canning to surveying to smithing to herbalism. I clicked on the heading for “Toys,” and that’s where I found it: a trove of late-19th and early-20th-century books, advising children on how to make their own toys at home.

Survivor Library is an archive, but it’s also something of an argument for reversion to an older way of life. The inclusion of late-19th-century books on “morality,” and of many 100-year-old textbooks covering American history, paints a picture of post-apocalyptic Americans rolling back the clock in their social relationships while learning how to use plows with horses again. Books make their way into this archive in part because they are in the public domain, so the choice to include these may have been in part a pragmatic one. Even so, the idea of a future where people revert to the beliefs of mainstream Americans, ca. 1900, is nostalgic for some and horrifying for the rest of us.

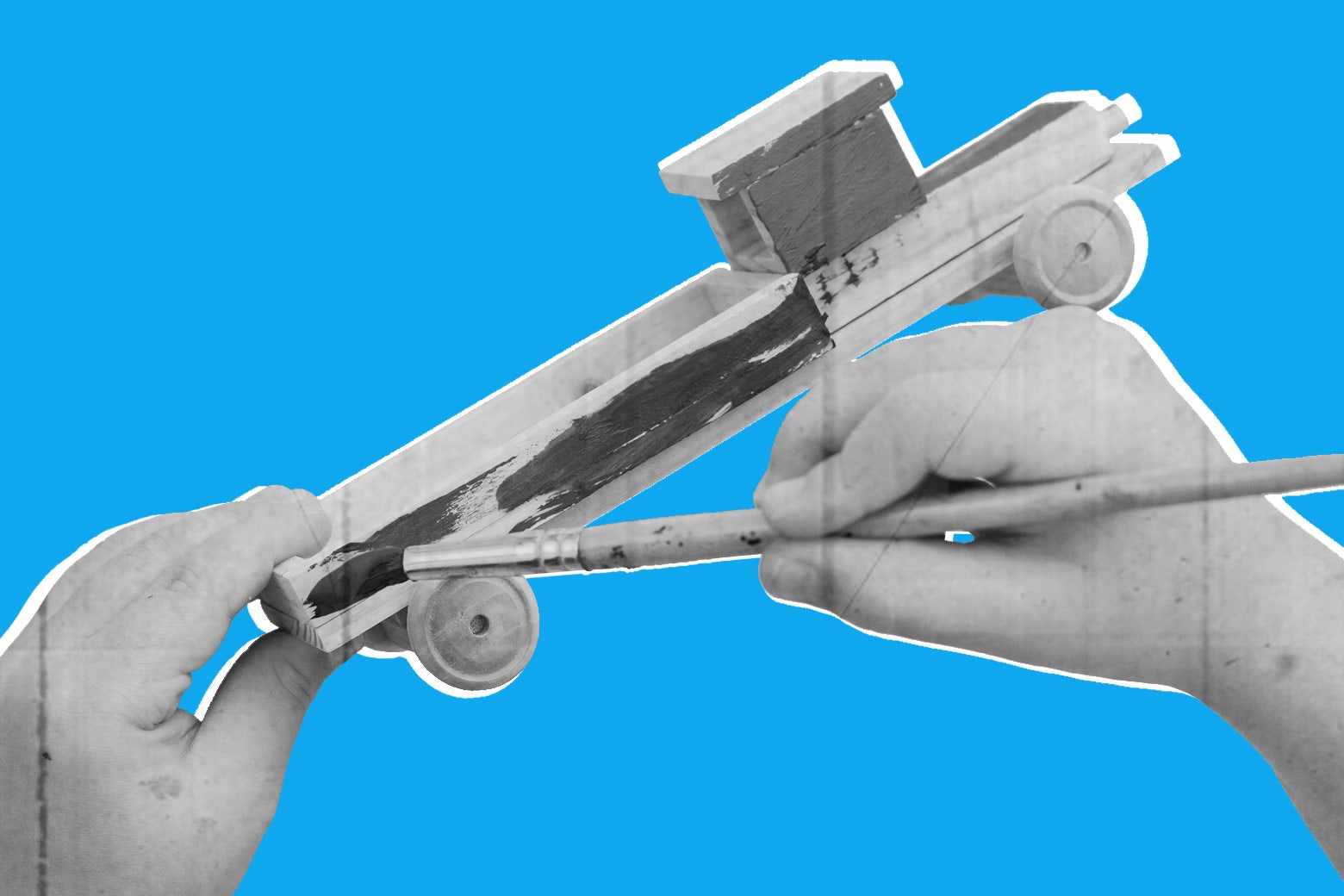

At first glance, these Make Your Own Toys books evoke only that nostalgia. Looking at these books in mid-December, as I struggled to keep my own toy purchases under control, the idea of 19th-century children constructing their own playthings—probably by the fire, while calmly listening to their mother playing the piano—is eminently appealing. But as with many things in the history of childhood, children’s toy-making was less idyllic than it seems.

It’s hard for a modern parent to fully grok the paucity of toys in Colonial American households. Historian Karin Calvert points out that in the Colonial period, “neither playing games nor possessing toys was considered inherently childish by definition,” and the most expensive store-bought toys were made for a wealthy adult market. Children whittled wooden whistles and pinwheels for themselves, when they were allowed, but they were often employed at jobs inside the home—and sometimes forbidden to play by religious parents, who believed it to be frivolous.

Looking at portraits of children of elites, Calvert noticed an increased presence of toys around 1770, and a concurrent increase in expectations that childhood was a time for play. But in the first half of the 19th century, American homes—especially the poorer ones—were still relatively barren of playthings. In her history of dolls, Miriam Forman-Brunell cites memories recorded by Harriet Robinson, a “mill girl” growing up in New England. Robinson “had no toys, except a few homemade articles of our own. I had but a single doll, a wooden-jointed thing, with red cheeks and staring black eyes.”

Even kids who had access to rare, expensive, fancy toys were, it seems, not likely to play with them too often, preferring their homemade playthings, which came with fewer restrictions. In her memoir New England Girlhood, which described her childhood in Massachusetts in the 1820s and 1830s, Lucy Larcom wrote of her “ragchildren.” Larcom described these as “absurd creatures of my own invention, limbless and destitute of features, except as now and then one of my older sisters would, upon my earnest petition, outline a face for one of them, with pen and ink.” Nonetheless, Larcom loved the “absurd creatures” “far better than I did the London doll that lay in waxen state in an upper drawer.”

At this point, children making toys for themselves at home was still a matter of necessity—not of adult prescription. The earliest example I found of an adult moral argument that kids should make their toys came from writer Maria Edgeworth. In her Practical Education (1815), Edgeworth suggested giving children supplies—“card, pasteboard, substantial but not sharp-pointed scissors, wire, gum and wax”—when they were too small to use saws and planes. Kids could use these tools to make models of furniture, architectural forms, and models of simple machines, “choosing at first such as can be immediately useful to children in their own amusements.”

This edict was in line with Edgeworth’s belief—later to be repeated again and again by Progressive Era educators—that overly “finished” toys bored children, and that boredom made them petulant and disagreeable. A “baby-house” could be a good toy if unfurnished because it prompted children to make things to fill it up, Edgeworth wrote; if provided full of furnishings, it was “tiresome” and would not be played with for long.

The Civil War marked something of a watershed for the industrially manufactured children’s toys’ market. Before the war, few kids might have had store-bought toys; afterward, the expansion of industrial capabilities and innovations in materials brought more and more “adult-made” toys into children’s lives. Historian Howard Chudacoff describes this as a transitional period, when children’s toys were a mishmash of the self-made and the mass-produced. William Allen White, a journalist who grew up in Kansas in the 1870s, remembered “homemade sleds, wagons, bows and arrows, as well as the whistles, stick horses, and ‘little railroads with whittled ties’ ” that he made for himself. Bellamy Partridge, who grew up in the 1880s and whose father forbid him to play cards, took dominoes and secretly made them into a deck—showing that children’s toy-making wasn’t always inherently virtuous.

Adult claims for toy-making as an educational practice also increased in this period, and it became clear that the strict gender divides of the second half of the 19th century would find their own manifestations in toy-making. Ebenezer and Alice Landells, in their The Girl’s Own Toy-maker, and Book of Recreation (1860), stipulate in their introduction that girls should learn to make such items as doll’s clothes, baskets, and pincushions to develop their aesthetic judgment and prepare to decorate their own homes when they grew up and got married: “Nothing is more becoming than to see a home neatly and tastefully embellished by the handiwork of its inmates,” they wrote. Girls who knew how to make things out of paper and cloth could make their homes pretty, craft presents to give their friends, or have “the pleasing gratification of adding by their skill to the funds of some charitable or benevolent institution.”

Meanwhile, the Landells had a different pitch for the boys. “Many of our young friends have no doubt heard their parents join in the lament that has been made by some clever men on the general want of knowledge of ‘common things,’ ” Ebenezer Landells wrote in the introduction to The Boy’s Own Toy-Maker (1860). “Who,” they asked rhetorically, “would be the more useful person of two cast on Robinson Crusoe’s desert island—the man who could only speak Greek and Latin, or the boy who, in hour of need, could erect a little hut or even construct a boat from the lessons learnt in play-hours?” For boys, the Landells believed in time spent learning how to use a saw or make a model of a ship with full rigging.

As the 19th century moved into the 20th, the old tradition of home toy-making took on more moral significance for Progressive Era reformers who were interested in anchoring children in everyday “doing,” while leading them away from the pleasures of shopping. Late-19th-century mothers in the American upper middle class, Forman-Brunell writes, “took doll manufacturers to task by rejecting their products,” preferring “cloth dolls that taught virtue and understanding.” Fancy Gilded Age dolls “that reflected conspicuous consumption, ritual, and display” were out. Forman-Brunell cites advice writers who suggested that “making dolls rather than indulging a love of dress and finery would prevent degeneration into godless anarchy.” These people, in other words, were also nostalgic for earlier times; we aren’t the first generation to wish our children’s playroom shelves were barer.

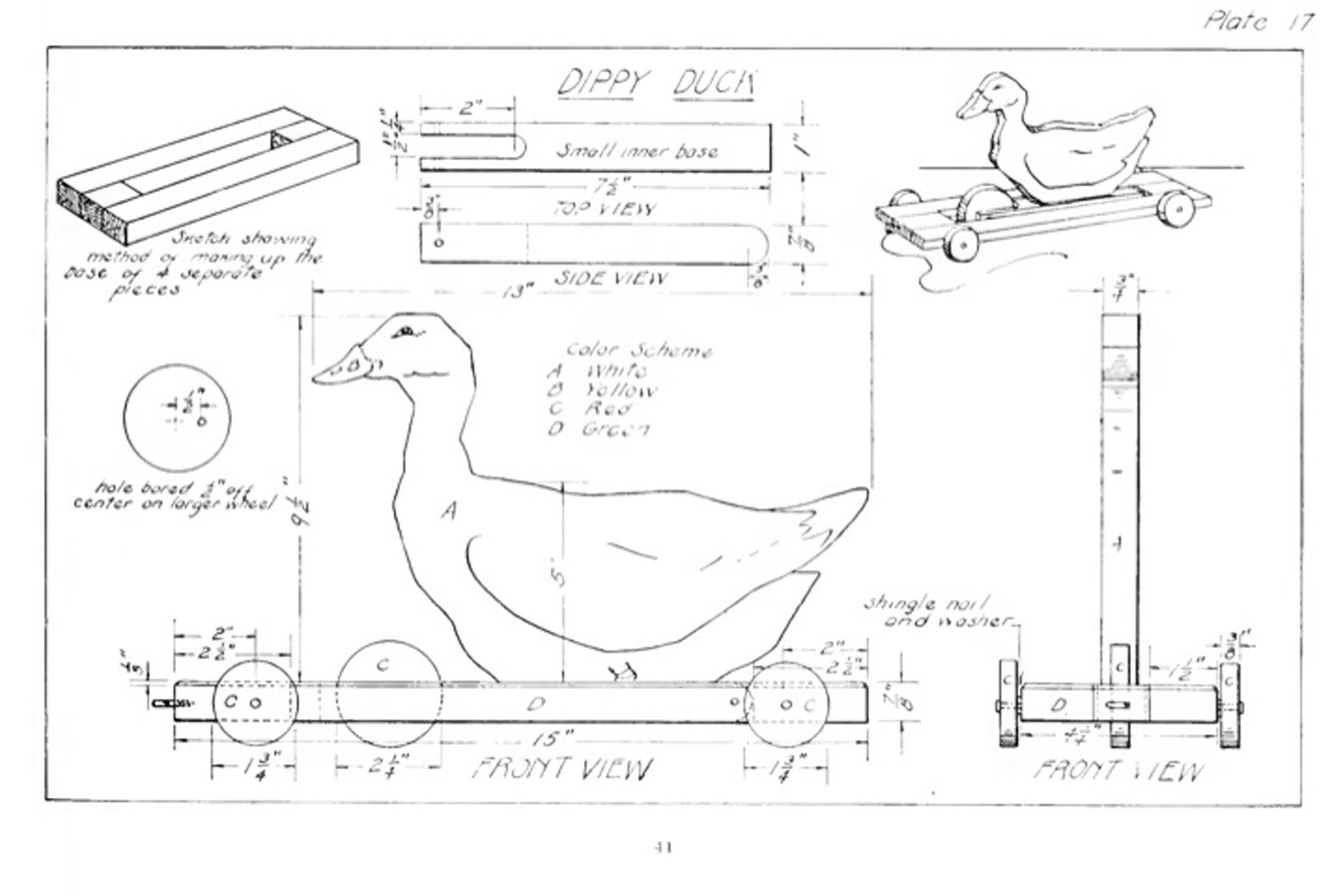

Several authors of these early-20th-century books that form the bulk of the “make toys at home” literature were teachers of manual training, a precursor to vocational education that drew inspiration from Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi. The manual training movement incorporated wood and metal work into typical curricula, and, unlike later models of vocational training, was designed to further liberal arts teaching rather than replace it.

The list of things that home toy-making was supposed to teach was long. Thrift: “[Children who make their own toys] will learn a lesson in economy they will not forget, a lesson they can apply to real work as well as play work,” Carrie Williams wrote in Tin Can Toys and How to Make Them (1916). Patriotism: Mabel E. Turner wrote in an introduction to Leon H. Baxter’s Toy Craft (1922), “Of how much greater value is one such plaything actually put together by a child than any number of toys made in a factory or imported from some foreign country?” (Before World War I, many manufactured American toys came from Germany.) Carefulness: Leon Baxter wrote, “Each year American parents spend millions of dollars for toys for the children. In a short time a large part of these toys are broken, and lie in the corner or the back yard. This is because of the destructive habits children have developed. These same habits have been formed because, since birth, toys have cost these children nothing.”

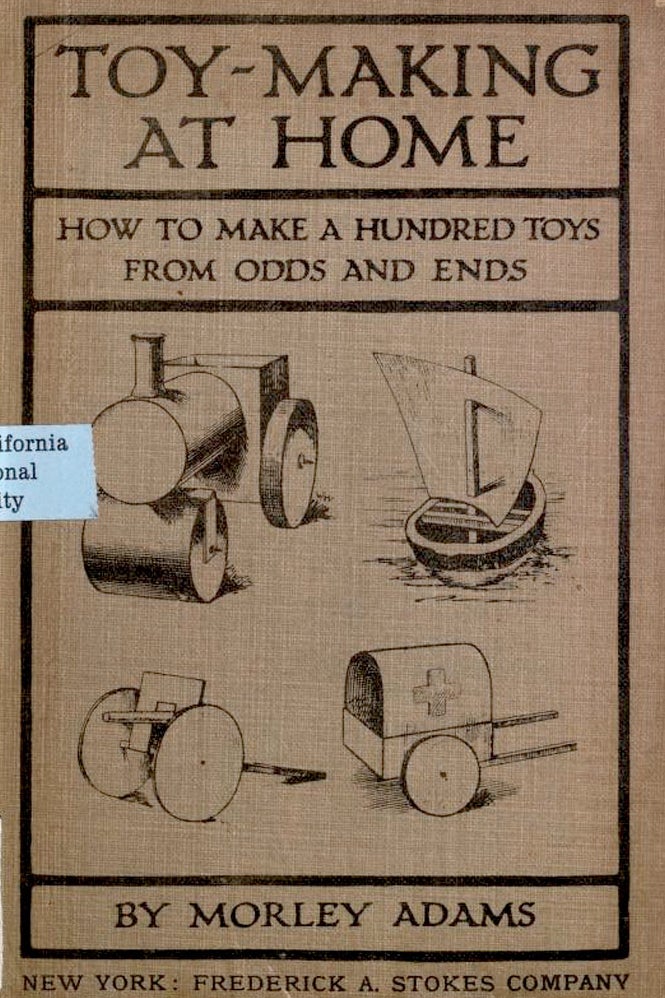

People in the early 20th century perceived the world as increasingly full of waste. Food was more likely to come in packages from the store, and more and more manufactured items were available to the typical consumer. Toy-making children could, in a very specific sense, help their households hew more closely to the model of domestic economy previous generations knew well, where most things were reused instead of thrown away. Morley Adams wrote in his Toy-Making at Home (undated, but probably early 20th century), “In every household there are countless things which are thrown away immediately they have served one purpose.” These—Adams listed cotton-reels, matchboxes, broken clothes pegs, mustard tins, eggshells—were the debris of a society that had more and more sloughed-off material to spare. Homemade toys were a chance for kids to close the loop.

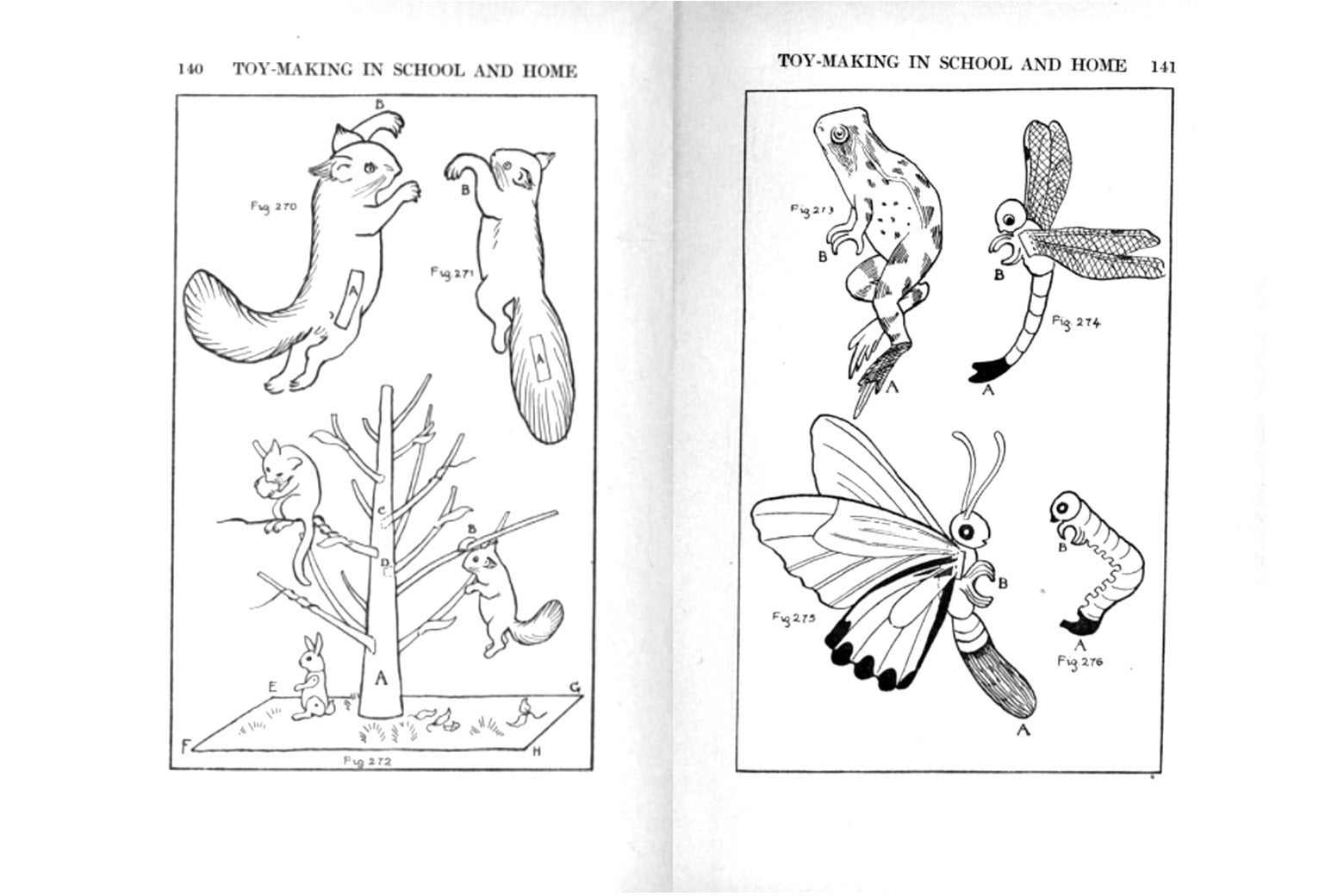

Some of these Progressive Era educators, unlike the more stringent Landells of a few decades before, were forward-thinking in their prescriptions for girls interested in making toys. “The girl who has had a course in handwork” or woodworking, argued R. Bassett, an English secondary-school headmistress, in an introduction to Toy-Making in School and Home (1916), “does take a more intelligent interest in things around her.” That girl was good at failure and has what we would now call “grit”: “She does not give up in disgust. … She finds out the cause of the failure and tries again and again until she gets better results.”

Bassett thought that women were “often limited in their amusements and their hobbies” because of the many tools they didn’t know. “How helpless we are with a screw or a saw, how futile our attempts to adjust a loose door-handle, or to set the knives of a mowing machine!” Bassett fretted. “It is humiliating to call for help in such simple jobs, and tantalizing not to be able to enjoy the carpenter’s bench as our men-folk do in their hours of leisure.” The cultural belief, inherited from the Victorians, that girls should be most interested in sewing and working with paper, were limiting the lessons girls learned from making her toys: “The little girl deals with ‘wee’ things: stitches are small, dolls are small; there is a fatal tendency sometimes to ‘niggle,’ to ‘finick’—not that men-folk are immune from this—to love uniformity and tidiness for their own sakes, to seek regularity rather than utility.”

The Progressive Era goldmine of “make your own toys” advice manuals and activity books had an afterlife—in Boy Scouts, in Girl Scouts, in 4-H groups. Homemade toys, Howard Chudacoff writes, were still fallbacks for families with lower incomes, even in the middle of the 20th century, as the market for children’s things expanded and mass production brought prices ever more down. Chudacoff refers to “testimonies by children” that mention “a companion doll made from straw and cloth rather than Patsy or Betsy Wetsy; building materials consisting of scavenged bricks or wood rather than Lincoln Logs or erector sets; games improvised from buttons or stones rather than formal board games such as Monopoly or Rook.”

So many toys of 2018—made of molded plastic, or embedded with electronics—are unmakeable by typical adults, let alone by children. Would we be better off if our children still made their own blocks, boats, and carts? Gather up cardboard, penknife, paste, and calico scraps, and make a dollhouse bed with your kids this holiday week. Good luck with that tiny pillowcase.