It’s the end of an era. Blockbuster, as we all once knew it, is no more.

On Wednesday, Dish Network, the parent company of the once-dominant video rental chain, announced that it would close all of its remaining 300 retail stores and would cease its DVD distribution centers by early January 2014. Its remaining Blockbuster @Home streaming service will continue.

“This is not an easy decision, yet consumer demand is clearly moving to digital distribution of video entertainment,” said Joseph P. Clayton, Dish president and chief executive officer, in a statement. “Despite our closing of the physical distribution elements of the business, we continue to see value in the Blockbuster brand, and we expect to leverage that brand as we continue to expand our digital offerings.”

Thirteen months ago, Dish gave up on the DVD-by-mail strategy that it had hoped would take on Netflix.

A drop in the bucket for Dish: Blockbuster lost $35 million in 2012

Three years ago, when Blockbuster declared bankruptcy, Dish Network swooped in to acquire the video rental chain for a final price of $234 million. The plan was that by using the footprint of those stores, Dish could sell mobile devices to stream Blockbuster movies. But the Federal Communications Commission has been taking longer than expected in deciding whether Dish should be allowed to use its satellite spectrum for that purpose.

“You make a lot of mistakes in business,” Charlie Ergen, Dish’s founder and chairman, told Bloomberg in an October 3, 2012 interview. “I don’t think Blockbuster is going to be a mistake, but it’s unclear if that’s going to be a transformative decision.”

More recently, though, Blockbuster sustained a $5 million net quarterly loss for the second quarter of 2013. (That’s still better than the $13 million loss it had during the corresponding period in 2012.) Overall in 2012, Blockbuster lost $35 million for Dish.

But don’t cry for Dish: the company as a whole profited $1.2 billion last year alone, and it has raked in $9.3 billion in profits from 2008 through 2012.

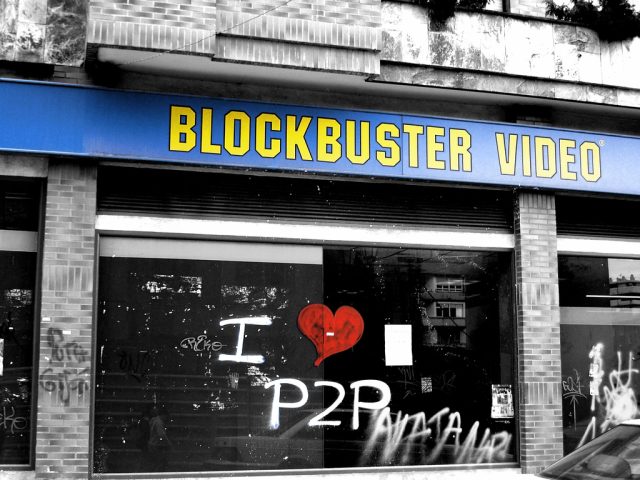

In the company’s most recent annual report, a 10-K filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Dish said that it closed 700 Blockbuster stores in 2012, “leaving us with approximately 800 domestic retail stores as of December 31, 2012. In January 2013, we announced the closing of approximately 300 additional domestic retail stores.” (One of those closures included my neighborhood Blockbuster Video here in Oakland, which shut its doors in late 2012.)

The company added:

Factors that are unique to the Blockbuster business, compared to our existing businesses, include, among other things, maintaining adequate inventory, controlling shrinkage due to theft and loss, managing excess inventory, product fulfillment and operating losses. If we are unable to successfully address these challenges and risks, our Blockbuster business, financial condition, or results of operations will likely suffer.

Long before the bankruptcy, Blockbuster had been struggling to regain its footing. It launched its own Netflix-style clone in 2004. It got hit with a lawsuit by Netflix in 2006 (they settled a year later).

On May 7, 2012 a company called c4cast.com sued Blockbuster for violations of its patents—the case appears to have settled as of August 2013. There are also a number of other similar pending patent cases against Blockbuster, according to the company’s 2012 10-K filing.

“Our Blockbuster business faces risks, including, among other things, operational challenges and increasing competition from video rental kiosks and streaming and mail order businesses,” the company added, noting that its remaining assets are worth over $357 million as of the end of 2012.

An Ars editor’s five months at Blockbuster, circa 1995

A few Ars staffers had fond memories of renting from Blockbuster in our youth, but Joe Mullin, our tech policy editor, actually spent five months of his teenage years working at one location in Orange, California, outside Los Angeles.

He writes:

Blockbuster was the second job I ever had, and the first job I ever got drug tested for (because marijuana and movies are a dangerous mix). I took the job in 1995 on a recommendation of a high school classmate, who sold me with three simple words: "It's so easy." Re-stocking videotapes for $4.25 an hour sounded like a better deal than the $4.40 an hour I was earning at a pizza place doing actual hard work, like preparing food and washing dishes. I wouldn't come home smelling funny, and they'd give me five free rentals a week. I was sold.

My Blockbuster memories say more about life at minimum wage than anything about the chain in particular. Workers were allowed virtually no autonomy, even for tiny decisions. Reversing a mistaken computer entry, forgiving even a $1 late fee—everything required a manager to be summoned. I studiously avoided developing the single "skill" we were asked to cultivate, which was the fine art of offering suggestions to customers who couldn't find popular movies that were out of stock. (We're out of Dumb & Dumber? Try Ace Ventura: Pet Detective!) If we accidentally rented more than our five free rentals a week—a new, generous level of benefit that had been installed before I was hired—we had to pay full price, no takebacks. Managers were measured by how many "overrides" they did, and they would never do one for an employee.

I remember being told to greet each and every customer that came in the store—"Hi, how are you?" eventually devolved to just a reluctant "hey"—my one and only experience with what I would later come to see as a bizarre American-ism. I was struck at how easy it was for customers to successfully argue their way out of late fees and even make far more specious arguments ("Your tape broke my VCR, and you guys had better repair it!").

Blockbuster may have been doomed, but you wouldn't have known it back then. We were the most popular store in Orange, California. The "New Releases" shelf (which held movies as old as a year) had just lackluster choices by the end of a Saturday night. Determined customers waited for their movies by the return box, hoping to see if a popular movie had been returned in the nick of time.

If you have any other Blockbuster memories to share, you know where the comments section is.

reader comments

126